The following post was written as I started working on my book The Pop Musical. Sweat, Tears and Tarnished Utopias, published by Columbia University Press. It has been slightly edited but it still reflects the ideas I wanted to address as the writing process started.

Elvis Presley in King Creole (Michael Curtiz, 1957)

Most accounts on the movie musical have discussed the classical version of the genre in a way that meant privileging a certain approach to audiences (“mainstream” audiences, which in the classical period were not distinct from “mature” audiences), a relationship to Broadway and jazz traditions and certain relationship between “script” and “musical” elements (sometimes moving clearly into “attractions”, sometimes aiming for some kind of “integration”). They seem warier to engage with pop and rock. Of course, the types of music in those labels have been driving the music market since the mid-1950s, so we might as well explore the ways they have influenced the evolution of the genre.

Furthermore, looking back at the genre from the vantage point of 2022, one realizes that this has not been the prevailing mode for musical films at least since the late 1970s. Jazz and Broadway music have become rarer in the movies, whereas disco, Latin rhythms, or hip hop, are featured more frequently. Whenever Broadway music is featured, for every musical film in the Broadway tradition (say, Sweeney Todd, Chicago, or Into the Woods), we get several films based on shows that captured pop styles (Dreamgirls, Rent, Hairspray, Hedwig and the Angry Inch). Even original Hollywood musicals, like Moulin Rouge, are also more likely to draw from the pop catalog.

Finally, film and TV look at pop music for inspiration more than they used in the classical period: 8 Mile, Empire, Glee, The Get Down, even Smash, a TV series on the production of a Broadway show, had to introduce a “pop” strand in its second season.

The Teen Beach Movie (2013), a tribute to the 1960s "Beach" cycle

Pop music replaced Broadway as the main source for hits from around 1960. Pop musicals, from the Elvis Presley or Frankie Avalon vehicles to Dirty Dancing, 8 Mile, or Footloose, seem to respond to a different set of expectations. Whereas some historians use “pop” in a general sense to signify “popular music”, there is something distinctive in a strand of pop music that rises, to use the date proposed by Bob Stanley (in Yeah Yeah Yeah. The Story of Modern Pop), around 1955.

This marks the year of mainstream visibility of rock and roll as a cultural trend. Soon studios would try to catch up (somewhat patronizingly at first) with the trend, releasing a cluster of Elvis Presley and other “youth-oriented” musicals. Pop music (rock and roll in the late 1950s) blurs, according to Stanley, the distinction between “black” and “white” music (which was so powerful in old studios), as well as national distinctions (pop music is global) and, at first, it creates a gap between the young and more mature audiences (rock is for youngsters and screaming girls according to mainstream Hollywood, which targets mature audiences). Pop also develops its own marketing dynamic and star personae.

Although Hollywood will want in, and pop music has a place in Hollywood productions (as early as 1956 in films like The Girl Can´t Help It! or the Elvis Presley series), the fact is that for a while this approach seemed out of place in musicals and non-musical films. Pop seemed too determined by youth audiences and Hollywood had not quite decided to address films specifically to this audience niche (here I take Stephen Tropiano’s point in his book on the youth movie Rebels and Chicks that “youth” audiences are discovered, with a bit of alarm at first, around the time of Rebel Without a Cause in 1955). And there was a snobbish attitude towards rock and roll from the old guard of the rat packers and crooners.

Dreamgirls (Bill Condon, 2007)

Barry K Grant’s 1986 article "The Classic Hollywood Musical and the 'Problem' of Rock 'n' Roll" articulated some of the issues of Hollywood adopting the new style. A recent book on the Broadway musical by Mark N. Grant also addresses the differences between rock and traditional show tunes and accounts for the way they achieve different aims.

Nowhere are the tensions between old and new trends as clearly articulated as in George Sidney’s 1963 film adaptation of the 1960 Broadway show Bye Bye Birdie. The inspiration for Bye Bye Birdie is Elvis being called to the army in 1957, thus leaving teenage girls in America forlorn. But its attitude towards pop music is patronizing: pop is superficial, puerile, and silly, whereas the Broadway songs and stars (Dick Van Dyke, both in the show and the film version) are sophisticated and do things with a certain elegance and eventually carry the day. In an opening montage, the frowning face of Frank Sinatra is juxtaposed to the hip-swiveling Elvis lookalike.

At the same time, there is some irony in the fact that Hollywood could not ignore rock, it made use of pop singers (Bobby Rydell) and created a bona fide youth star in Ann-Margret. By the early 1960s, the new pop music dynamics gained force steadily and there are numerous pop “waves” as rock and roll is followed by doo-wop, the Beatles phenomenon, Motown, psychedelia, soul, disco, hip hop, techno, etc. Still, until the 1970s, these attempts will not define musical film.

Clive Hirschhorn’s comprehensive The Hollywood Musical (written in 1980), which aims to include every musical film made until that moment, considers pop and rock musicals “fringe”, and many of these were manufactured as cheap cycles, as for instance the Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello films of the mid-1960s.

Taron Egerton in Rocket Man (Dexter Fletcher, 2019)

Pop-youth stars like Connie Francis in the 1960s were featured in several films, but they were not always musicals. In short, for a couple of decades, pop and musicals were kept distinct strands. There were exceptions. In Britain, Richard Lester tried to harness the energy of the Beatles phenomenon in Help! and A Hard Day’s Night. And by the early 1970s, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, and David Bowie had made inroads into the movies and rock was more and more prominent.

Still, when one thinks of musicals, mainstream, Broadway-based sounds and stories come to mind: The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, Oliver, Mary Poppins, and Fiddler on the Roof were the great hits, and pop music personalities always seem to be tourists in Hollywood films.

More and more pop musicals are made in the early seventies (Tommy, Rocky Horror Picture Show, Saturday Night Fever) as a result of a stronger focus on the youth market. Pop music is normalized in the movies, sometimes as nostalgia (American Graffiti), but one film seals the fate of the movie musical placing it firmly within the artistic and commercial structures of pop.

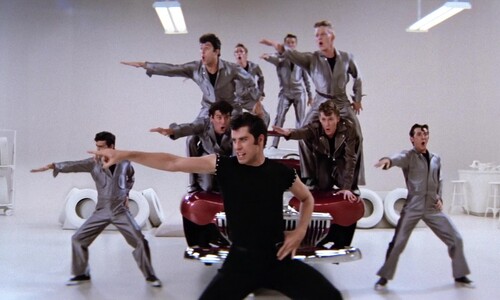

John Travolta in Grease (Randall Kleiser, 1978)

The film was Grease, starring a pop star, Olivia Newton-John, based on an off-Broadway show which used pop sounds circa 1958, produced by a record manager, with new songs by pop writers (such as the Bee Gees), and addressing “youth” audiences. Grease becomes the blueprint for later pop musicals. Although its closest follow-up, Can't Stop the Music, was a huge flop, it influenced the approach to musicals in the next decade.

In a recent conversation at The Other Palace, in London, wunderkind Manuel-Lin Miranda and legend Andrew Lloyd Webber agreed that musicals should reflect "the kinds of music people actually listen to". The next step is, of course, to make inventive, dramatic use of it.

And this is probably the key to the history of the relationships between pop and the musical: how to make tunes not conceived as dramatic material fit a dramatic context.

John Cameron Mitchell in Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001)