Words like "autobiography", "self-indulgence" and "testament" often come up when people talk about All That Jazz. But Fosse died eight years after the film was released (and almost thirteen years after the events the film recreates), so referring to this film as a "testament" might be premature. And as Fosse remarked, self-indulgence has close links with artistic expression, particularly when the work is very personal. Yes, he's telling us about things he cares passionately about, mostly himself. So, a certain self-indulgence needs to be noted.

Bob Fosse: 1974, 1979, 1987

As for the "autobiography" bit, well, some facts are undeniable. It's true that Leland Palmer and Erzsebeth Foldi play characters inspired by Gwen Verdon and Nicole Fosse, that Ann Reinking plays someone very much like, er, "Ann Reinking"; the film's editor Alan Heim plays an editor (also Lenny's editor), Jessica Lange had had an affair with Fosse, Cliff Gorman says some things Dustin Hoffman said or might have said and stars in a film which, like Lenny, is about a standup comedian; there are rumors that John Lithgow could be Hal Prince, that the Anthony Holland character writes a tune very much like Jonathan Schwartz's "Magic to Do" from Pippin (and are there hints of Fred Ebb also?) and Mary McCarthy is seen in the same room as the model set of Chicago (where she played Mama Morton) joining a cast that resembles that show's dramatis personae. Last but not least, "All That Jazz", everybody knows this today better than they did in 1979, is the opening song of Chicago.

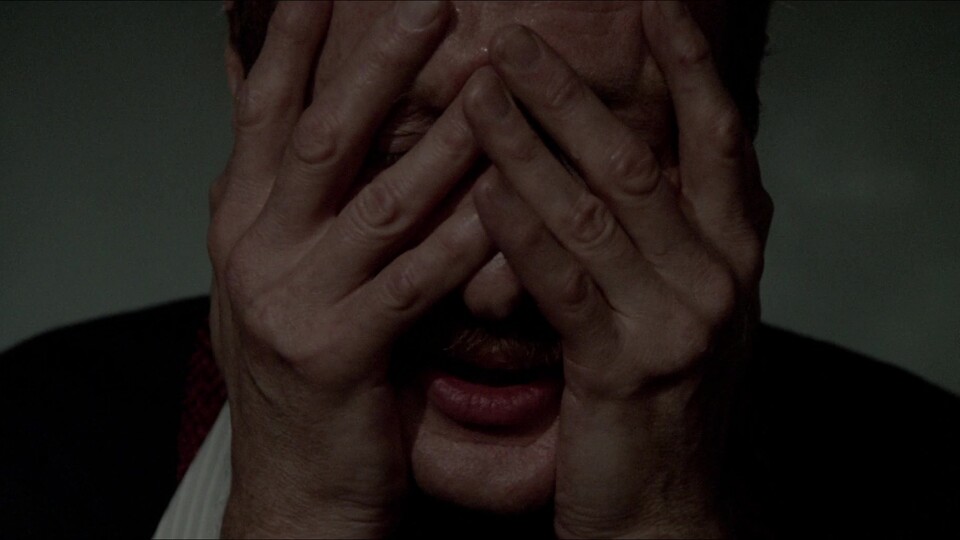

Besides, Fosse did go through some (well, most) of the things that happen in the film.And although Roy Scheider insisted Joe Gideon was something between Fosse and himself, the fact is Scheider was not a workaholic womanizing choreographer who had a heart attack while he was working on a Broadway show and doing the final edit of a movie. Still, things are hardly ever as simple as all of this would suggest and I think the best way to understand the film's relationship with reality is an anecdote Scheider told at a Fosse memorial in 1987: after shooting the fabulous section in "Bye Bye Life" when Gideon goes up to greet friends, family, colleagues and lovers, Fosse told Scheider that must have been exhilarating, and when the latter said, "yes sure, you should try it", Fosse, after some hesitation, did. "You were right", he said, "It felt terrific".

All That Jazz 1979

Broadway Rivalries

So, yes, All That Jazz is fiction, but somehow it is a fiction Fosse felt about very strongly, and it was fiction born out of lived experience. Given the technical impossibility of raw accounts of the self, the film actually becomes more autobiographical when it is blurry (or dishonest) about the details. Would All That Jazz be possible without Fellini's 8 1/2? Possibly. Fosse's admiration for Fellini is palpable here, and his first film and one of his greatest Broadway hits had been an adaptation of Le Notti di Cabiria. But All That Jazz is not a straight adaptation, like Maury Yeston and Arthur Kopit's Nine, and there is more Fosse than Fellini in the plot, structure, and aesthetics. I am not even sure that the Fellini film constitutes the original inspiration. Even before his heart attack in November 1974, he had already chosen a book about dying, Ending, by Hilma Wolitzer, as the basis for his new project.

But maybe the key inspiration was Fosse's frustration at not having come up with A Chorus Line ("A good concept for a musical", he said). Chicago, after a notoriously problematic production process, turned into a (reportedly) wonderful show, it opened in March 1975 to good reviews... which were promptly forgotten, like everything else, when the phenomenon A Chorus Line, which had opened a week before at Joe Papp's Public Theatre, transferred to Broadway a few blocks away, and then went on to sweep the board at the Tonys and everywhere.

Fosse could not conceal his jealousy of Michael Bennett. Chicago closed after a healthy 923 performances, whereas Bennet's show was still going in 1979 and finally closed after 6137 Broadway performances. It shares with All That Jazz a fascination with musical theatre as something essential to life, indispensable to our psyche, that goes beyond mere entertainment. In A Chorus Line, dancing has a deep meaning. It becomes a metaphor for all kinds of passions, the kinds of things that give meaning to our lives and in the process end up trapping us.

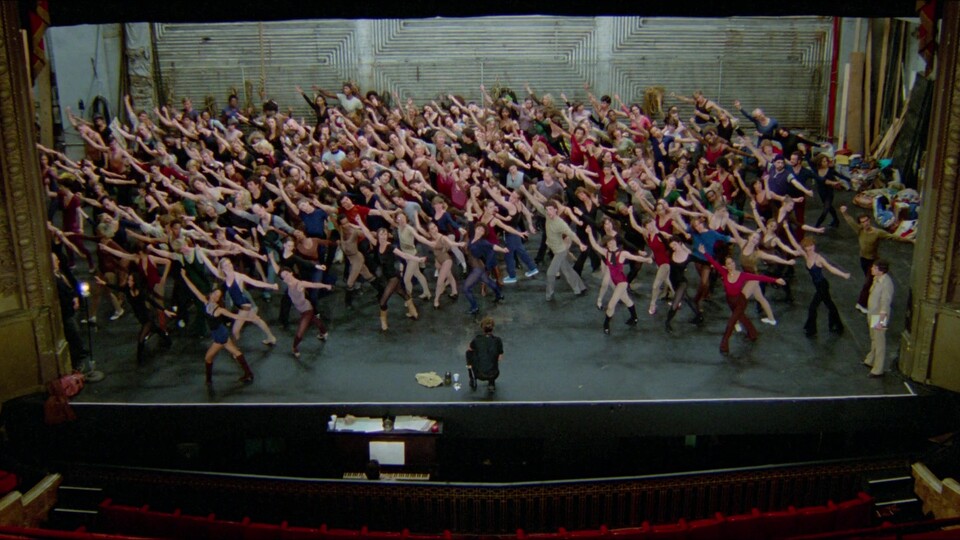

There's also that opening number, to the tune of George Benson's "On Broadway", a typical Broadway cattle call, exquisitely shot, more vividly truthful about art and struggle than the two-hour of platitudes articulated in La La Land. Everybody felt Fosse wanted to do a Bennett here. Even Bennett. It is a "diegetic" number, but the dancers only occasionally follow the music we hear, maybe it is not even what they are hearing. There is in Giuseppe Rotunno's cinematography a documentary feel that seems to whisper in every image: "What you're witnessing is a slice of life". The editing, however, does follow the music: the structure of the number and its rhythms are musical and we would feel this even if no music was playing. And even if the dancing lacks the long, perfect, convoluted movements of an original Fosse choreography, it does things that Bennett could not do on stage: focus on the faces, pick up particular dances, guide our attention, and cut rhythmically. "I Hope I Get It", the opening number of A Chorus Line was surprisingly inventive. I think "On Broadway" does something masterful in cinematic terms. Now, compare "On Broadway" with Richard Attenborough's version of "I Hope I Get It" in the woefully misguided film version of A Chorus Line... and what comes to mind is Fosse's self-satisfied smile.

All That Jazz, 1979

Dancing as Metaphor

The final number in A Chorus Line (like the final number of All That Jazz or similar moments in Follies) is a painfully ambivalent statement on whether the whole thing was worth it. Maybe, that ending seems to be implying, getting what we wanted is never as fulfilling as we thought, but it is the only thing we can do. "Bye Bye Life", gravitates around the same questions, although it's more emphatic and more ego-centered.

Something movingly conveyed in both numbers, clearly, is the choreographer's love for the dancers. It is a very special kind of love: father love, teacher love, there is admiration, there is pain, Fosse and Bennett looked at dancers and knew what they were doing, knew about their vulnerability, their joys, their commitment, their sense of inadequacy, their short professional lives. We tend to take for granted chorus dancers in a show as if their only function is to entertain us while we wait for a big emotional star moment. And it is moving that Fosse here (as Bennett on stage) is so intent in reminding us of everything dancing is all about.

From the opening number on, All That Jazz will seldom focus on dancers again, but the dialogue with A Chorus Line lingers. Ostensibly, the film is about Joe Gideon, not a very nice man, as Fosse himself would acknowledge, in the midst of editing his latest film, The Standup, and casting a show that looks a bit like Chicago and sounds a bit like Pippin. This guy is obsessive, he is hard-working, he is also a liar, self-centered, self-destructive, and wounded.

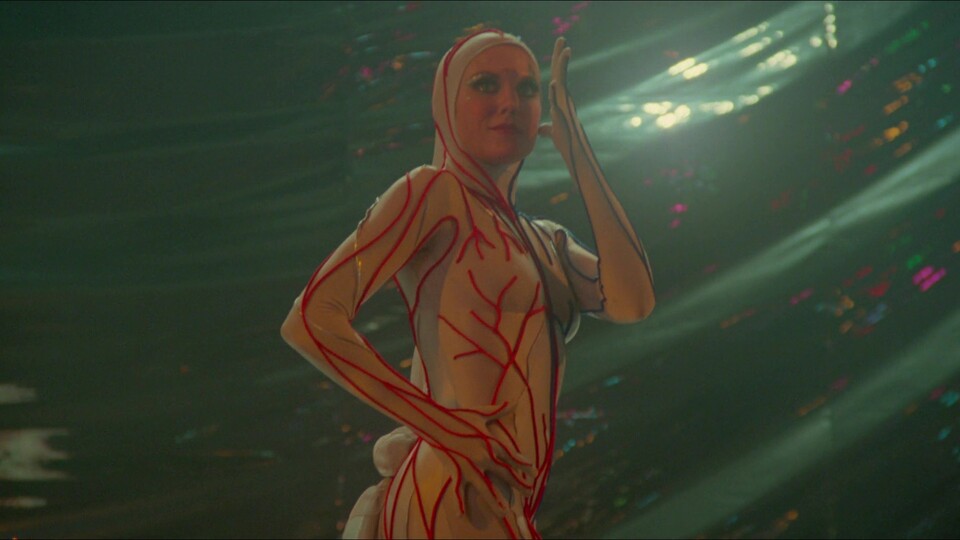

A parallel strand in the film, has him talking to a beautiful mysterious woman in white, sometimes adding an explicit layer of irony to the story. Commentators have read Jessica Lange simply as "death". I would argue this is a bit more complex. A couple of times, it looks like she is about to give him "the kiss of death" (clearly after the last number), but Angelique is also passion, she's also life, she's the woman desired, the one who will not believe Joe, who will remain skeptical, who will not fall into his web of lies. She's almost the opposite to the Spider Woman: she makes Gideon be what he is. She's a metaphor for some kind of beyond, but it is a metaphor that belongs to Gideon and that makes the whole difference: death is something that happens to the character, whereas Angelique is some deathly principle within the character.

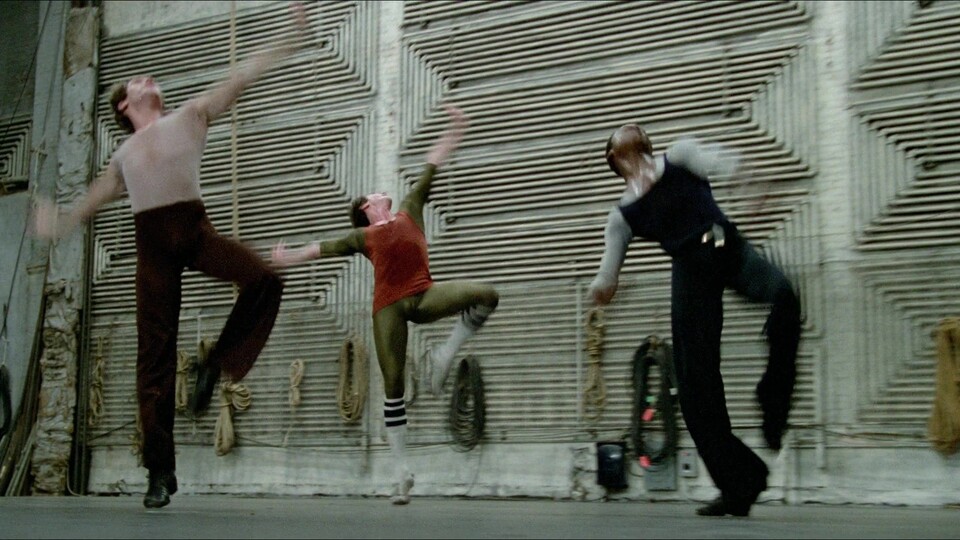

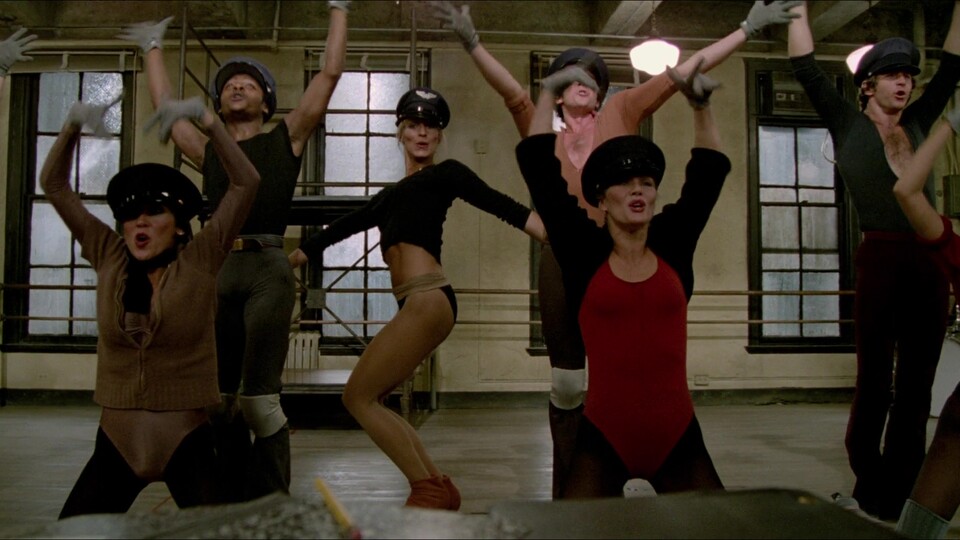

So there is something in this story that is not quite a series of events, and maybe that's the part of Fosse which is not Gideon. The rest of the film shows aspects of Gideon's life, we witness the creative process and the way art arises out of most everyday materials. All That Jazz is a very sweaty film, we can see at every turn how art takes work, how a lot of it has to do with preparation, rehearsal. In her influential book on the musical, Jane Feuer gave us the insight that classical musicals hid the effort and of course characters never sweated. Rehearsals often appeared as fully formed numbers. Here, in the rehearsal room or in the hospital fantasy sequence we see dancers focusing, taking their positions, getting ready before dazzling us.

We only see one "finished" number in the film and it is not something that has been put together in a rehearsal room, it is a projection, some kind of statement both inside and outside of the story we have just witnessed. "Bye Bye Life" The film ends with one of the most extraordinary musical numbers ever shot. It is about parting. Ostensibly about death ("I think I'm gonna die") it is also, very emphatically, about life, in the same way as "One" in A Chorus Line was both about the mundane and about the exceptional.

So the number reads like sex: an explosion, something confusing, noisy, elegant, hungry. There's Ben Vereen, who was a sinister Leading Player in Pippin and has something of Cabaret's MC; there are the two girls (one of them played by Ann Reinking who is both "inside" and "outside" the number, sitting in the tiers), the Vegas costumes, the very fond, very moving farewells, beyond good and bad. Yes, John Lithgow is there, but also the Verdon and Nicole figures (the funny, detached, glowing shot of Leland Palmer holding back tears and sticking out her tongue is one of the most heart-wrenching in American cinema of the seventies). The pulsating rhythms in the music and in the dancers remind us of heart's pumping, grabbing on to some kind of life principle, but also of how precarious that life principle is.

And over everything, there is the way to live, all clothed by showbiz which is both a metaphor but also something very real. The number uses the flashy razzle-dazzle that Fosse had commented on, cynically, in Chicago. But here something else is at stake as if having second thoughts: one perfect number, one big moment seems to actually give meaning to the plot; razzle-dazzle may be just surface, but what else is there, how else do we communicate, how else do we manage to "be".

"Bye Bye Life" does not produce a satisfactory, logical ending in a narrative sense, but it does make a very strong statement about Fosse and the show business tradition he represented. After "Bye Bye Life" we cannot feel nihilistic. We are somehow satisfied, we know what it was all about. As Fosse pretending to be Gideon during the shoot, something tells us this must have meant something after all.

All That Jazz, 1979