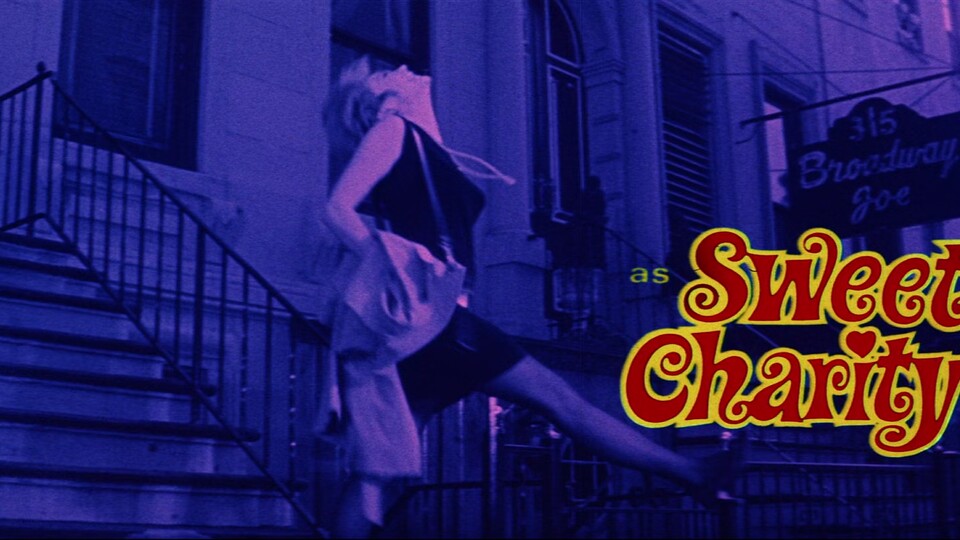

Before its official release, word of mouth for Sweet Charity was very good. Bob Fosse's film version of the 1966 stage musical written by Neil Simon with a score by Cy Coleman and witty, slangy lyrics by Dorothy Fields, was expected to be a success. The property had reached some popularity on Broadway, some of the songs had been covered by pop stars like Shirley Bassey, the film was also very "now" and was alive to the times when pot and sex were beginning to be cool. And it had a big star. Not the biggest box office attraction, but, really, few female performers could open a film at the time (and a wide eyed prostitute was certainly not a role for Julie Andrews, who was still riding on her mid sixties successes). Then it opened.

And not only people were not interested. The film was dismissed as "elephantine", "boring" and "too brassy". Reviews were lazy and largely disengaged. It's true they had some reason to be.

As Matthew Kennedy points out in his book Roadshow!, The Sound of Music seemed to suggest big musicals were a winning formula, and suddenly everybody wanted one. Maybe "big" is not a condition for musicals, maybe it was not done very well, but Dr Dolittle, Paint Your Wagon, The Happiest Millionaire, Hello Dolly! or Star! all bombed in spite of talent and sometimes solid material. And when Charity finally screened, it seemed to follow the trend, critics felt it was a similar case: the musical was dead after all. Not that the film is perfect: it's true that the script is clever but heavy going, and the film overstays its welcome. It's not the size, it's the length that may make it hard to take.

On the other hand, Sweet Charity is among the best musicals of the decade, certainly more innovative than My Fair Lady or The Sound of Music, it developed a post-1968 sensibility and it had a point of view and a look that did not look back to the pre-war years.

And then there's those numbers. Bob Fosse was logically contacted to direct (as he had directed the stage version) and, initially, he hesitated, which was logical. He was at a good professional moment on Broadway and he had developed for Hollywood the kind of attitude disgruntled lovers develop: he admired everything about it but feel rejected and misunderstood, so he did not want to have anything to do with it.

In the project, he had the inestimable help of cinematographer Robert Surtees, fresh out of The Graduate (a shot of Charity seen through a fish tank could be his signature) who was allowed input and created a style which was fittingly shrill, colourful (with a distinctive red and black palette) and managed to balance out grit, expressiveness and comic book visuals. So, the film uses real shots of New York Streets which suggest documentary ("this is just a girl who lives in this city, could be you") and then a series of techniques that suggest that this is subjective, that it is the world as felt and experienced.This approach works particularly well during the musical numbers.

And then it had Shirley MacLaine, an admirer of Fosse's work from her early years (she had understudied in Fosse-choreographed The Pajama Game before going to Hollywood), aware that she was filling very big shoes (after all it was originally a Gwen Verdon role, and Verdon was universally adored) and of her limitations and professional throughout. MacLaine had a certain china doll quality that worked very well with her prostitute roles, and here she approaches the role with intensity and simplicity: radiant smiles, brimming with joy, or crying streams of tears, effervescent throughout.

If Charity was a normal movie, one could argue she was trying too hard. But Charity was a very stylized musical, and those excesses, here and in the sets, cinematography, music, were an integral part of the project. Charity boasts great musical numbers which are, in conception, effectiveness, and realization among the best in the history of musical films in the specific ways they try to be cinematic.

"Hey, Big Spender" reprises ideas of the original Broadway staging (the contrast between stasis and frenzy, the long line of hookers) but uses the camera to emphasize faces, personalities, movement. Like the other numbers in the film, it is not about an event, but about a state of mind. He represents these women both as seen from outside and in their inner turmoil, as reality and as imagination.

"If They Could See Me Now" is a cute solo number for MacLaine and she puts in it all of her repertoire. I like the way it moves from a very stagey set to the close-ups and how we shift between the objects in the room to her inner joy. It does stop the action, but I think it is the fault of Peter Stone's talky script. We don´t need to spend so long in that room. Yet I would not give up one single shot of the number.

"I'm a Brass Band" is probably the most daring number in terms of conception, and it does something very few numbers had done until then: forgetting any kind of continuity between spaces or actions. It is almost abstract. Although musical numbers are associated with the unreal, the fact is they tended to respect literal spaces except in dream sequences marked clearly as such. And even then the space had to have some logic. The ballet of An American in Paris, to compare this to another number that happens across different spaces, has some kind of plot and something approaching a narrative thread, that establishes links between the parts. Here the changes respond to Charity's imagination running wild with joy at being loved. So we move from Brooklyn Bridge to the Yankee Stadium to the Met to Wall Street just because these places are grand enough or showy enough as a set for her. The only logic here is emotion.

Emotion explains the dancers, the musicians, the movements, the sets, and the shots. And in terms of the final result the real masterpiece, probably among the best five numbers in the history of the genre, is "There's Gotta Be Something Better Than This". As in "Brass Band", there is a certain disjoint quality about the spaces. The number starts in the dressing room, then moves downstairs to the dance hall, repeats the setup of "Big Spender" and then goes back upstairs to the roof. There is something of a tribute to the equally superb "America", which also is scored to a Latin beat, yet the whole feeling here is different. In a typical Broadway move, this is a "I Wish" number, only it comes halfway through the show. Interesting, as the desires of the characters, won´t help us follow the plot. Yes, they want to leave, but they know they won´t. And then there is the actual dancing.

Both Paula Kelly and Chita Rivera, who carry the number with MacLaine have a wonderful screen presence and Fosse knows them and loves them well enough to show us every simple gesture, every precise line reading. The dancing is vital, dramatic, and one can see there's more to these women than we thought. The number is about emotion and character, and every shot, every configuration of colors, limbs, smiles, fingers, and mascara is flawless. One could argue the film is not about very much.

One could argue the film is not about very much. And yes, most of those 1960s musicals do have an empty heart. We don't get the point of Star!, of Dolly, of Camelot. And the accusations of flashy spectacle rings true. But Charity does have a heart.

Call it the Broadway ideology. It's about the role of illusion in keeping us alive. Fosse's philosophy would evolve from the early 1970s and, from Pippin onwards, it linked the joys of show business somehow with death. Not here. There may be a certain irony, a drop of cynicism, but overall Fosse believes this works for certain people and it's better than nothing. And surely nobody could present the idea more flawlessly.