The Spanish title for the Morton DaCosta film version of Meredith Willson's 1957 Broadway hit The Music Man was "Vivir de ilusión", which translates of "Living of illusion" or "Life is a fantasy", and for once the change in the title was appropriate to convey what the film was about. It also shows that the translators really understood what the film (and the show) was about. A clear defense of fantasy worlds against the dreary, much duller forces of reality is one of the key promises of the musical as a genre: outside, it's winter, but here it's very hot; forget your troubles and just get happy; our dreams are more romantic than the world we see; every time it rains it rains pennies from heaven; razzle-dazzle 'em: look to the rainbow... we could go on forever.

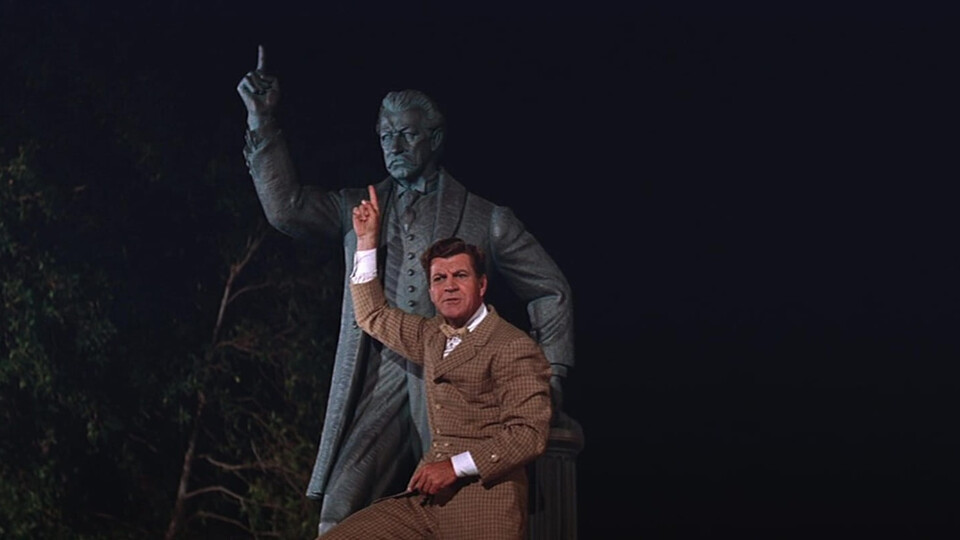

Robert Preston in The Music Man

Musicals are filled or reminders that imagination can conquer reality, that it is somehow better. Maybe this is the central idea that has come to characterize the genre best in histories and genre assessments and in the minds of fans. Descriptions of the musical as a utopia point in that direction. Yet this idea was conveyed through specific songs rather than stated as the show's philosophy as if, in the last analysis, it was considered too counterintuitive to base the film's plot on that idea.

Is The Music Man (Broadway 1957, Hollywood 1962) the first instance where this idea is presented literally, almost nakedly, as the true meaning of the plot? This post argues that, even if the promotion of fantasy had been there from the start, this is a pivotal show in making this clear and produced a strong descent of similarly themed shows. Like any really great musical, The Music Man uses music as a metaphor (rather than just background or spectacle), which is articulated precisely in the plot, numbers, and styles. The protagonist is a charmer, a liar, and a swindler. He even lies about his name, which is not Harold Hill.

Besides musical instruments, he sells a fantasy of what musical instruments can do to a community, a fantasy which he obviously cannot fulfill, and other traveling salesmen complain he is giving a bad name to the profession. Yes, he does get people what they pay for, but after all, a flute is just a wooden cylinder unless one knows how to play it, and instruments in themselves do not make music. He arrives in River City, a rural, conservative town in Iowa, with the firm intention of conning the population into buying musical instruments and uniforms then leaving without really telling them how to use them. He uses the kind of panic about what young people do when not at home which was gripping America in the wake of Rebel Without a Cause (West Side Story will use that same panic in a different way): so rather than listen to the radio (or TV in 1957 America) they could focus on old fashioned community values and form a band.

Great idea, which everybody buys: modernity must be resisted at any prize, and the music promoted is bland, more inspired by John Philip Sousa and Gilbert and Sullivan than by Elvis. This has the seeds of satire on consumerism; it could be the story of people who buy things they don't need. But this is the interesting thing. Willson develops the premise not towards criticizing consumerism but toward valuing illusion. Buying things people don't need and staving off modernity ends up being a good thing in this community. Towards the end, the conman cashes in and is about to skip town, but is caught before he manages to go. He has fallen in love, you see, with the town's librarian, and listening to the wide-eyed, sentimental, beautiful "Til There Was You", has delayed his escape. When he's about to be tarred and feathered (frontier punishment), River City realizes that the fantasy they had harbored about being a musical community has magically come true, and music has impregnated the whole social life: gossipy women do dancing, the school board becomes a barbershop quartet, and, yes, kids form a band without having taken one valid music lesson.

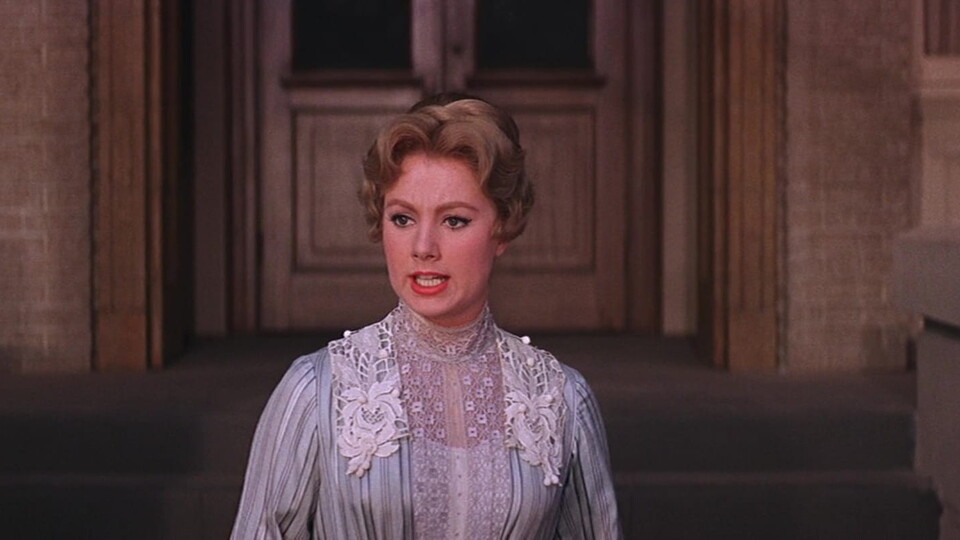

The Music Man (1962)

This is validated by the librarian. Being into Balzac or Rabelais and lending books has made her into something of an outcast in River City. Two other things are important about the character: she gives piano lessons and therefore is "musical" when Hill arrives. And he has a little brother, Winthrop, with a lisp who is painfully shy. Somehow as the town is filled with music, she'll realise how the change is making things better and helping little Winthrop. She will not only fall in love with the charmer but will make a case for him, pointing out that even if he is a liar, River City owes him the joy of music. Few musicals are as radical in expressing this (potentially reactionary) idea as The Music Man.

Of course elements of escapism had always been implicit in the genre. The Ziegfeld Follies presented fascinating images of womanhood, and so did the Busby Berkeley movies; the grace of Fred Astaire conveys the kind of elegance that, given the choice, people might want to adopt, and so on. The idea is there in On the Town (perhaps) and is more clearly articulated in Finian's Rainbow but then shunned or rejected in the "integrated" shows by Rodgers and Hammerstein. Even in West Side Story, in spite of "Somewhere", the whole point is about engaging with reality, rather than providing a safe alternative to it. But it is important for me that very few shows before The Music Man actually said that fantasy was somehow preferable.

In 1962, another play had something really interesting to say about fantasy. The title teased audiences as if daring them to live without illusions, something that, it was assumed, would be impossible, although by the end of the play the main characters will have to try. It was, of course, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, that would explore the darker side of the American dream. But the fantasy of The Music Man kept on being seductive. So, truth or illusion, do we know yet? For some people, this is precisely the problem with American culture, for others its saving grace. Harold Hill could be Oprah Winfrey. He could also be Donald Trump.

The Music Man opened on Broadway the same year as West Side Story, and it provides a completely different direction for musical theatre, to the point that the fact that it was the Willson show rather than the Robbins one has been read in terms of preference for more populist approaches and maybe the beginning of the decline historians describe during the 1960s. West Side Story will push the musical into Fiddler, Cabaret and Company, whereas The Music Man will pave the way for Mary Poppins, The Sound of Music, The Happiest Millionaire, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Dr Dolittle or Hello Dolly!, films that believe in the triumph of fantasy. It is certainly the beginning of a self-conscious strand in the Broadway musical that engages with the alternative of fantasy. It is also the necessary formulation of an ideological agenda before reaction arises, as cynicism or anger in the work of people like Sondheim, Fred Ebb, or Bob Fosse.

Cynicism is at the heart of Follies and Chicago, and in general, it dominates the gritty, tarnished shows of the 1970s. Maybe the most articulate and popular counter-statement to the illusions promoted by The Music Man is Herbert Ross' film version of Dennis Potter's Pennies From Heaven. This of course illustrates that there is no stable ideology to the genre, that utopia can be created, but also demolished through song.